Breaking the rules

The rules of composition

Most ‘How to’ books on painting or photography will have a section fairly early on about composition, that is, what to include in the work and how to arrange those elements on the picture plane so that they look good in the final piece. There are a couple of age old formulae for this, called the golden section and the rule of thirds. In simple terms the picture plane is divided into three’s, for example in a traditional landscape painting the land would take up the lower third of the painting and the sky the remaining two thirds. If there was a prominent feature in the painting such as a church steeple, it should never be central despite its importance, you are advised to locate it approximately a third along either from the left or right edge. This formula of course is merely advisory, but if you keep reasonably loosely to this blue print you will end up with a very satisfying composition.

Another piece of compositional advice is that that a successful landscape should in theory have a foreground, a middle distance and a background, again excellent advice, except that many beginners put too much detail into their foreground and spoil a perfectly good piece of work.

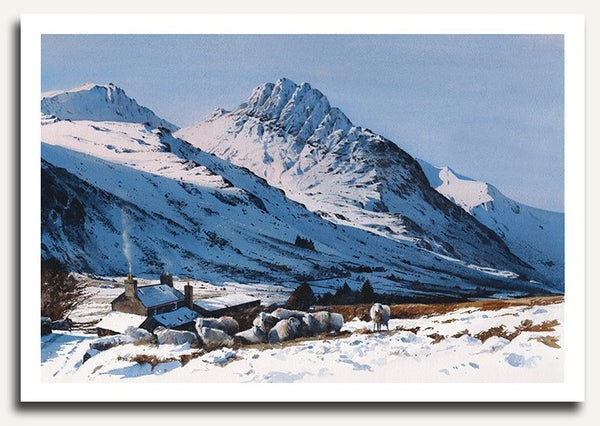

Here is an example of a traditional landscape with one third land and two thirds sky. The most important feature, Cricieth Castle, is located two thirds of the way from the left edge. Notice also that the painting has a foreground, the castle in the middle distance, and Moel Y Gest and the Moelwyn mountains in the background. All the elements that fits into an acceptable landscape.

Breaking the rules to paint dynamic and powerful mountain landscapes

Mountain landscapes however have their own set of rules, or rather lack of rules, because all of the above quite frequently goes out of the window. In the context of this blog I consider a mountain landscape as one which has been painted either amongst the mountains or, on them, preferably high up, rather than the rather picturesque depiction of the mountain from the valley, where you could apply the formulas mentioned above. The benefit I gained from painting scenes which I thought early on as being quite challenging has provided me with a wealth of compositional resources, some quite unconventional.

Early in my painting career I poured through many painting technique books which of course tend to use the 'Rule of Thirds' method of compositional planning and I must admit it served me well for many years. It was only when I started combining my mountaineering with my painting that I started to play around with my composition, mostly out of necessity. I found at first that I still tended to look for a scene with a foreground, middle distance and background, something I still do in fact, especially if the foreground has relevance such as in the painting of Tryfan below.

Ditch the foreground

Apart from the sensational views, being 3000 feet up a mountain has other benefits none more so than being able to look steeply down a mountainside, perhaps at a ridge snaking away towards another distant summit, or maybe to a lake enclosed within a corrie or cwm. Very often the views afforded to you from high up often across a deep valley towards another group of mountains are inspirational, but they can be a long way off with no suitable foreground available.

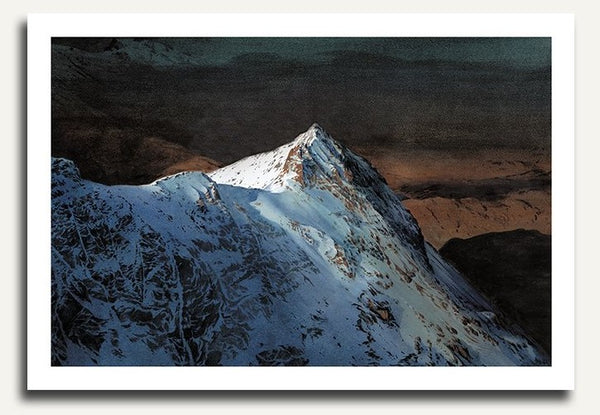

The painting below is of Crib Goch, without doubt my favourite mountain, it is part of the Snowdon range and is a fine example why sometimes foreground are totally unnecessary.

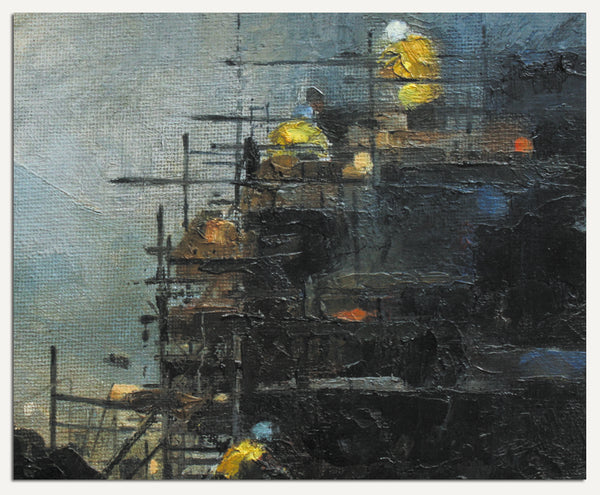

A group of friends and I decided to go up Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon), it was quite late when we set off and we had accepted that we would have to descend in the dark. When we arrived at the summit, in deep snow, the cloud had descended and we could barely see each other. This was the time when they were demolishing the old cafe and building a new one, so there we were sitting knee deep in snow surrounded by building paraphernalia and machinery, very weird.

Just as we were preparing to descend the cloud miraculously lifted and exposed this wonderful view of Crib Goch, brightly illuminated by the sun setting in the west, standing out remotely against the dark sunless valley below, wonderfully inspiring.

When I returned to my studio I decided to paint it exactly as I first saw it without a foreground to detract from the the grandeur and dignity of the mountain standing remotely against the darkened valley.

It remains one of my favourite pieces, a painting which I chose as the cover of my book - The Snowdonia Collection.

As an aside, I was so taken with the absurdity of a building site on the summit of a 3500 foot mountain that I vowed to go back and record what was happening there, below is a small oil painting, just one of many I completed at the time.

Use linear features

Between the main Snowdonia summits in the north and Cader Idris in the south of the national park lie the lower hills of Merioneth. These summits are conveniently arranged in a long chain of tops running north to south, the southern tops are grass covered and easily traversed, whereas the northern tops are anything but. Known as the Harlech Dome, they have been compressed into a torturous mix of folding rock making progress very difficult. Amazingly land owners have built a stone wall along part of the crest of this range of hills, which I have often used in my paintings. Below is a large oil painting showing how a painter can create great dynamism from looking down and along a snaking ridge, (including the stone wall,) the lake adds another element to the scene. Notice that the painting has no foreground and it does not lose anything from this because of the ridge providing a linear feature that leads the eye along from the bottom of the painting to the distant peak of Llethr, in fact the lack of a foreground enhances the great feeling of depth and distance in the piece because your eye is immediately drawn to the ridge climbing away from you. Any foreground detail would detract from this illusion.

The 'sublime ' in art

The Romantic painters of the mid 19th century actively sought out these high peaks in search of the sublime. It was fashionable to depict landscapes which were dark and threatening. One of the characteristics of the sublime movement was that many compositions had little or no sky and when it was included it was often cloud covered, such a difference to the Picturesque painters who preceded them. You can easily get away with painting landscapes with no sky, especially if you are high up looking down into a valley or cwm.

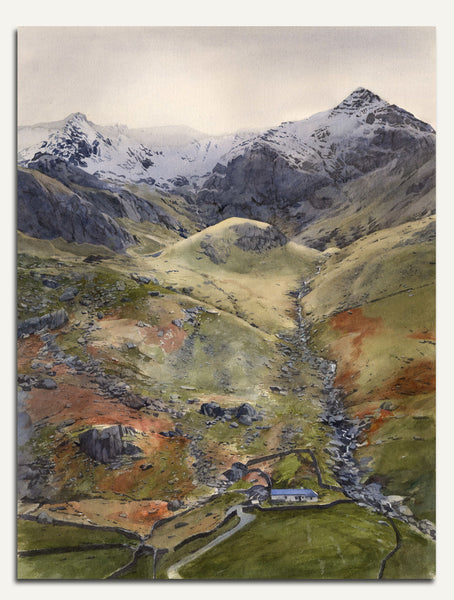

The painting below is a fine example of this, although it does include a sliver of sky. It is the view from near the summit of Pen yr Oleu Wen looking down into Cwm Idwal with its legend shrouded lake.

This, I must admit, is quite an extreme representation of the genre and people either love or hate the painting because to some the feeling of tremendous exposure induces a feeling of great anxiety, but to others it mimics the feeling of actually being there (without the slog)

Contrary to what I was saying about ditching the foreground earlier some compositions cry out for it. Here I've included a rocky pulpit as a foreground and this serves two purposes. First of all without the darker crevices and other detail of the pulpit the painting would tonally be very flat and lack impact, and secondly unlike the previous painting it has no naturally occurring land form to lead the eye away into the distance.

Looking up

The opposite of looking down steeply, of course, is looking up steeply and I have incorporated this compositional format into my armoury as well. The Llanberis Pass is a well known feature in Welsh mountaineering folklore, mostly because of its important in the development of Welsh rock climbing, it also connects the mountain village of Llanberis with Gorphwysfa, the most popular setting off point to climb Snowdon (known to most people as Pen y Pass) This glaciated valley is much narrower than its neighbour to the east, Dyffryn Ogwen, and as a result the peaks on either side appears to be higher and much steeper, you certainly have to stretch your neck to look at the summits.

Apart from Glencoe in the Highlands of Scotland there isn’t another valley in the UK which is quite as forbiddingly austere as the Llanberis Pass, it is almost bare of any vegetation and it is this bleakness that explains the attraction I have towards this valley.

Amongst all this expanse of bare rock though is a small oasis of greenery, where many years ago an individual had built a cottage and cleared a patch of land. It is now, like many such buildings, a mountaineering hut. Above this old farm the land rises steeply up to the ridge of Crib y Ddysgl 900 metres above in a little over a kilometre, it is an altogether magnificent setting and one which I have painted many times.

The painting above describes this scene, but to capture its unique steepness I had to climb up the opposite side of the valley for 50 metres or so, so that I could show the land around the old farm properly. If I had tried to paint it from the roadside that lovely area of green which is such a contrast to the rest of the painting would have virtually disappeared due to foreshortening. It also displays the insignificance of man amongst such magnificence.

I discovered this as a painting opportunity totally by chance. Many years ago when I used to rock climb regularly we would visit this crag in the Llanberis Pass called Carreg Wastad which looks down onto this old farm. The climb which we had intended to complete had a team already on it so we had to wait for them to get out of the way. As we sat there I noticed that there right in front of my eyes was this stupendous view and to make the scene even more dramatic the sun appeared and the cliffs of Dinas Mot (a spur extending down from Crib Goch) cast a deep shadow across part of the cwm, spell binding.

Panoramic formats

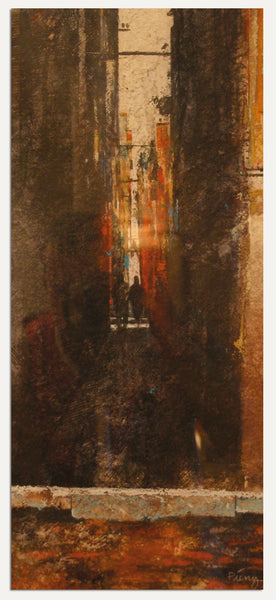

Another great way to add a punch to your composition is to ditch the standard rectangular formats and to paint tall thin pieces. This approach is excellent for depicting waterfalls and towering cloud formation, something you see often in mountainous terrain as the air rises dramatically above the peaks. Of course this is also a great way to paint old narrow street scenes. I've used such formats to paint many a Venice watercolour.

The opposite of this is the long, thin panorama and is definitely one of my favourite formats. This type of composition suits so many landscapes subjects, and within this scheme you can also play around with the elements that make up the composition. In the painting below I have applied a long, panorama format, but I have also decided to experiment with the elements as well. There is no foreground and the middle distance has been relegated to the very bottom of the picture plane, this give precedence to the distant view of the mountain slowly appearing after a snow shower has passed. This is really breaking compositional rules but I think in the right context it can work. You can use this approach to a traditional landscape as well. Ignore the one third two thirds composition and let that dramatic sky dominate. Go for a threequarter sky and a quarter land. Try it.