How to choose a watercolour paper

Despite the digital revolution and the popularity of social media, email and such like, we still produce an enormous amount of paper, and unless you live the life of a hermit you cannot escape coming into contact with the stuff.

Most paper produced in the world today is for commercial use and are derived from conifer trees. To make a ton of wood pulp for paper making takes 24 trees, and you end up with products such as news print, cardboard, toilet tissue etc, very boring, and a bit worrying.

However, not all paper manufacturers produce paper for toilet tissue and the gutter press because out there are paper mills which make beautiful paper, as beautiful as the art which it supports and this product is as different as chalk is to cheese from the boring stuff above.

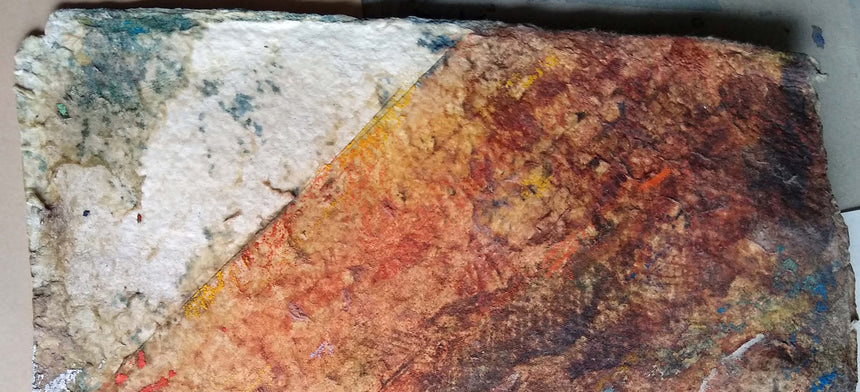

A beautiful handmade paper from the foothills of the Himalayas

Having said that both processes follow the same basic principles, the cellulose fibres from plants are macerated into a pulp then poured onto a screen, the water is allowed to drain leaving a soggy mess which eventually after drying becomes paper. There are three different methods of producing a sheet of paper, machine made, mould made and handmade. The commercial process obviously use machinery to achieve the large volumes necessary for that industry, the handmade process speaks for itself, each sheet is produced singly but you end up with a unique product, mould made paper falls between these two processes, but is more akin to handmade paper than those made on a machine. In this blog which is aimed at the budding watercolourist I shall be referring to mould made paper or handmade paper only.

Before getting to the practical issues of this blog I have to explain that most good quality watercolour paper are produced using cotton ‘linters’ pulp. Cotton linters are the unblemished bits and pieces left over after cotton is made into thread. Cotton ‘rag’ pulp is produced from old cotton material, clothing etc and is not so common. I don’t intend to go to any great length on the science of paper making, people have written books about it, so if you want to learn a bit more, get a book.

There are lots of very good watercolour papers available on the market today, and I’ve tried quite a few but eventually you have to decide which is for you. It is very much like my blog on watercolour paints, by all means experiment but you should eventually settle on a paper with which you will be completing most of your work. Don’t be misled by a beautiful handmade paper, many of them look absolutely wonderful, a work of art in themselves but hardly practical for learning the rigours of watercolour painting, I would recommend a stable mould made paper, with a uniform surface, it will also be cheaper.

Online shopping is very convenient, but when you’re initially looking for a watercolour paper it is far better to visit an art retailer where you can see and feel the different papers and get professional advice. There are, as I said earlier, many different producers of paper, and each one might have several different types of paper, all very confusing to someone intending to dip their toes in the water, so how do you choose?

Below I have outlined a few of the factors you should consider before selecting a paper. Let start by looking at the paper which I use - T H Saunders Waterford, which is at the top end of a mould made paper product. (Many other producers of art papers have similar ranges of paper)

The first thing you will notice is that the Waterford range comes in three different surface types :

- HOT This means that the paper has been hot pressed during the manufacturing process, resulting in a smooth, hard surface which is ideal for drawing on. It can also be painted on but be warned it stains immediately and the pigment is virtually impossible to remove. If you plan to start painting in watercolour stay clear of hot pressed paper until you’re confident enough to handle its challenging nature.

- CP NOT. Not quite sure what NOT stands for, NOT hot pressed perhaps? But CP stands for Cold Pressed. Anyway this is a softer surfaced paper with a slight tooth to it and as a result is more suitable for watercolour washes. This is the type of surface I would recommend to start your watercolour journey.

- Rough. Pretty obvious what this means. An excellent paper surface to progress to if you want to explore the medium a bit more.

Please note that these are very enlarged, in reality HOT pressed paper would appear virtually without any surface texture.

These three different surface types can also be divided again into different weights, measured confusingly in the UK and the US with the Imperial system of measurement in pounds (lbs) per ream (500 sheets) for a sheet of a certain size. These days most producers use the metric form and the weight of the paper is calculated in grams per square metre, which actually like most things metric makes more sense. For the sake of this blog what the watercolourist needs to know is how the different weighted paper performs and using the metric system, I have chosen four fairly common weights (thickness) 190 gsm, 300 gsm, 425 gsm and 640 gsm.

Most good quality office paper comes in at around 110 gsm which gives you an idea on our lightest paper, the 190 gsm. This is an ideal weight for sketching outdoors using very light washes of colour, and using small sheets of paper, because at this weight too much water would cause cockling and would certainly need stretching (this involves taping down the edges of the sheet with gummed paper onto a rigid board). The majority of watercolour sketchbooks are made of paper around this weight.

A sheet of 150gsm after applying a wash of colour to the top half. The paper has cockled badly making any further washes problematic.

300 gsm and 425 gsm are probably the most popular watercolour papers, every manufacturer produces a paper of this weight so it’s highly available, it’s also reasonably priced. I keep a good stock of 425 gsm HOT pressed papers in my studio, great for drawing or watercolour sketches, and if you keep your paintings quite small you might get away without any cockling. The larger the sheet you use to paint on the more extreme the cockling becomes.

This is a watercolour sketch on 300gsm paper. Notice the paper has cockled around the edges, this is because wet pigment has been applied to the centre of the painting only.

One of the unfortunate things about watercolour painting is that cockling of the surface is often unavoidable and can arguably be considered an unwanted part of the painting process, but what is also unfortunate is if you intend to sell your work the buyer will want a painting which is absolutely perfect, and anything but a perfectly flat image might be enough to put them off the sale. Sometimes I will paint on Khadi paper, a handmade pure cotton paper produced in the foothills of the Himalaya. It is a magnificent paper, I often wonder that if I put a frame around a bare imperial sheet, it would look quite acceptable. Unfortunately Khadi papers being handmade and allowed to dry outdoors do not lie flat and are inherently cockled. People might love the image but not the fact that it does not lie flat in the frame.

What do I think?

The majority of my work is done on 640 gsm paper and below I have drawn up a list of pros and cons of painting using this paper (it’s so thick you could describe it as a board, hold it by one corner and it barely sags)

Pros :

• You do not have to stretch it. Just get it out and start painting.

• If you make mistakes you can submerge the sheet in a bath of water to remove as much of the pigment as possible. Can’t do that if you’ve stretched it down on a board!

• You can use it to paint with oils or acrylic.

• Being so thick it’s also strong so it can take a great deal of repeated washes, this is because the paper I use is surface and internally sized. (Sizing stops the paint from being absorbed into the paper)**

• It never cockles, always remains flat, even a full imperial sheet (30” x 22”) (Some handmade papers are already cockled because of their manufacturing process.see above)

• It is easier to correct mistakes so despite its cost it can in fact work out the better buy.

• Owing to its thickness, in windy conditions two bulldog clips is all you need to keep it from flapping about.

Cons:

• More expensive

Conclusion

It all boils down to how much you are prepared to spend.

If you can afford it then go for the heavier paper, 640 gsm, it makes life so much easier, however if you need to look after the pennies then look at some of the middle range papers such as Bockinford, an excellent machine made paper. Again if you worry about spending too much go for a slightly lighter paper, say a 300gsm but bear in mind that this will probably need stretching.

This little experience might help you decide.

Recently a lady brought one of my old watercolours back to my gallery which she had bought twenty years ago. It was badly soiled after being exposed to a very damp wall for many years. After removing the painting from the frame, which had to be thrown away, the frame that is (kept the glass though). The back of the sheet , a T J Saunders Waterford, 640 gsm NOT had black marks where it had been in contact with the backing board (these days we would place a non acidic barrier board between the artwork and backboard). The image itself had slight damage, luckily not in the sky sector.

I was able to remove most of the black marks on the back by carefully rubbing it away gently with an eraser, noting that the dampness had not penetrated the surface, the damaged areas on the actual painting itself I was able to over paint. The painting has now been re-framed and is as good as new. I wonder how a lighter, non cotton paper would have held up to being exposed to such a soaking, not to mention the remedial work I had to carry out.